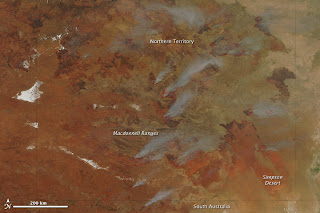

Large fires burned throughout Australia’s Northern Territory on September 30, 2011, when the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite acquired this image. The fires are marked in red. Fire fighters were monitoring 21 fires, said news report, but many more are shown in the image. The fires are burning through thick grass in remote areas.

Large fires burned throughout Australia’s Northern Territory on September 30, 2011, when the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite acquired this image. The fires are marked in red. Fire fighters were monitoring 21 fires, said news report, but many more are shown in the image. The fires are burning through thick grass in remote areas. The top image provides a closer view of three large fires around Alice Springs. The lower image shows a broader area of fire activity in central Australia. Smoke from the fires creating hazardous driving conditions in the Alice Springs region and forced some roads to close. Fires have burned nearly 150,000 square kilometers (58,000 square miles) in Northern Territory in September, said ABC News.

The top image provides a closer view of three large fires around Alice Springs. The lower image shows a broader area of fire activity in central Australia. Smoke from the fires creating hazardous driving conditions in the Alice Springs region and forced some roads to close. Fires have burned nearly 150,000 square kilometers (58,000 square miles) in Northern Territory in September, said ABC News. The fire season in 2011 is proving to be one of the most extreme in recent years. La Niña rains allowed thick grass to grow across Australia’s normally dry interior. The grass dried over the winter and is now an abundant source of fuel.